Hope! – Worthy of your attention

June 5, 2024

Hope! – Worthy of your attention

Quite frequently this website receives emails from LGBTQ Orthodox as well as their family members and friends in and outside of the Church, asking if I see any hope or signs that the bishops were either open to or making any changes when it came to their usual harsh rhetoric towards gay people. As Christians, we are called to be a people of hope. We hope for the resurrection of the dead and life eternal in Christ. We hope in our daily lives to live a life that Christ has called us to live, one that loves others and does not judge before removing the log from our own eyes. (Matthew 7:5)

Quite frequently this website receives emails from LGBTQ Orthodox as well as their family members and friends in and outside of the Church, asking if I see any hope or signs that the bishops were either open to or making any changes when it came to their usual harsh rhetoric towards gay people. As Christians, we are called to be a people of hope. We hope for the resurrection of the dead and life eternal in Christ. We hope in our daily lives to live a life that Christ has called us to live, one that loves others and does not judge before removing the log from our own eyes. (Matthew 7:5)

In this vein, I am always touched when I hear from those who are members of the Orthodox Church, and who are heterosexual, and voice their empathy and support for those of us who are LGBTQ and attempt to remain faithful members of Christ’s Church. There have been as of late supportive voices coming from the pastoral and scholarly worlds. Aside from academic works, the first few interviews are by a bishop and priests of the Church, expressing ideas rarely heard in the Orthodox Church. Also, Orthodox scholars in various fields of theology (biblical studies, patristics, church history, and ministry) have written articles and books, spoken at conferences, and in general, have been engaged in various corners of the Orthodox world on the topics of gender and sexuality. I would strongly encourage you to review the descriptions of the following interviews and books and consider reading the works in full to get a better understanding of some of the contemporary views of the Orthodox Church on the LGBTQ community, in particular those of us who are Orthodox Christians. (more…)

Four Weddings and a Funeral is a British movie, released in 1994, about the romantic adventures of Charles, played by Hugh Grant, and his lively group of friends as they support each other through a series of life events. Perhaps one of the most touching and memorable scenes takes place at the funeral of one of the friends, Gareth. It is revealed at the service that Gareth was not only gay but in a relationship with another member of the circle of friends, Matthew. In his eulogy, Matthew said “Gareth used to prefer funerals to weddings. He said it was easier to get enthusiastic about a ceremony one had an outside chance of eventually being involved in.”

Four Weddings and a Funeral is a British movie, released in 1994, about the romantic adventures of Charles, played by Hugh Grant, and his lively group of friends as they support each other through a series of life events. Perhaps one of the most touching and memorable scenes takes place at the funeral of one of the friends, Gareth. It is revealed at the service that Gareth was not only gay but in a relationship with another member of the circle of friends, Matthew. In his eulogy, Matthew said “Gareth used to prefer funerals to weddings. He said it was easier to get enthusiastic about a ceremony one had an outside chance of eventually being involved in.” Watching a documentary recently about the detrimental and life-threatening struggles thousands of homeless children face, I was struck by the following words of one of the counselors: “Be the person you needed when you were younger.” The often-quoted words are believed to originate from Ayesha Siddiqi, an author and children’s advocate. The counselor made this impassioned plea to those who might be able to support the admirable work of helping homeless children. Those of us fortunate enough to live in relative peace and prosperity rarely think, for very long, about those considerably less fortunate than us. Understandably, we get caught up in our own world and may only take a few moments to think about or help those less privileged and in need. To be sure, those needing everything from a warm smile, a compassionate ear to a good meal, are all around us if we just took the time to look and think and act. When we act, listen or think only a portion of the time about others, we are not being the person that others need.

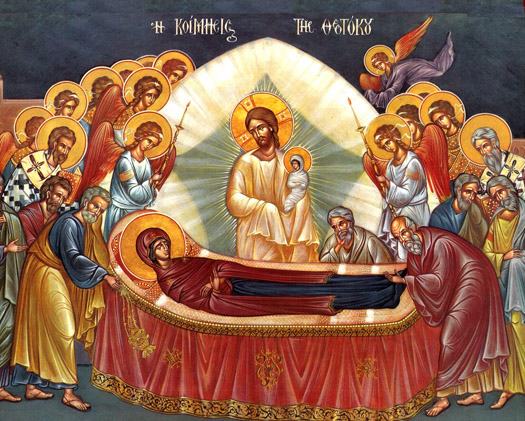

Watching a documentary recently about the detrimental and life-threatening struggles thousands of homeless children face, I was struck by the following words of one of the counselors: “Be the person you needed when you were younger.” The often-quoted words are believed to originate from Ayesha Siddiqi, an author and children’s advocate. The counselor made this impassioned plea to those who might be able to support the admirable work of helping homeless children. Those of us fortunate enough to live in relative peace and prosperity rarely think, for very long, about those considerably less fortunate than us. Understandably, we get caught up in our own world and may only take a few moments to think about or help those less privileged and in need. To be sure, those needing everything from a warm smile, a compassionate ear to a good meal, are all around us if we just took the time to look and think and act. When we act, listen or think only a portion of the time about others, we are not being the person that others need.  Through the generosity of the editors of “Orthodoxy in Dialogue,” we are pleased to re-post a wonderfully sincere and poignant piece entitled “A Gay’s Man Dormition Story”, published on their website on August 15, 2023, by an anonymous source. Please read the full article by following the link to “Orthodoxy in Dialogue” below, following the first paragraph of the work.

Through the generosity of the editors of “Orthodoxy in Dialogue,” we are pleased to re-post a wonderfully sincere and poignant piece entitled “A Gay’s Man Dormition Story”, published on their website on August 15, 2023, by an anonymous source. Please read the full article by following the link to “Orthodoxy in Dialogue” below, following the first paragraph of the work.

Seminarians, those preparing for the priesthood, frequently speak of having a “calling” to sacred orders. When I was in Seminary, the students often shared the moment, event, or path that led them to the desire to become a priest. Some stories were somewhat dramatic and could be tied to a specific time, others described a process, at times a lengthy one, culminating in them applying to Seminary. Each story was uniquely different and quite personal to each person. And even after years of arduous study, numerous liturgical services, private prayer hours, and participating in hours of conversations with those who would become lifelong friends, some concluded that they were not called to the priesthood. At the culmination of years at the Seminary, some were ordained, and others were never ordained. Each seminarian heard a different voice, a different calling from God, not only to enter Seminary, and “test” their vocation, but also discern when it was time to ask for ordination from the bishops. The same God was speaking differently to each of us, and we each heard different things, and acted in different ways, based on what we heard.

Seminarians, those preparing for the priesthood, frequently speak of having a “calling” to sacred orders. When I was in Seminary, the students often shared the moment, event, or path that led them to the desire to become a priest. Some stories were somewhat dramatic and could be tied to a specific time, others described a process, at times a lengthy one, culminating in them applying to Seminary. Each story was uniquely different and quite personal to each person. And even after years of arduous study, numerous liturgical services, private prayer hours, and participating in hours of conversations with those who would become lifelong friends, some concluded that they were not called to the priesthood. At the culmination of years at the Seminary, some were ordained, and others were never ordained. Each seminarian heard a different voice, a different calling from God, not only to enter Seminary, and “test” their vocation, but also discern when it was time to ask for ordination from the bishops. The same God was speaking differently to each of us, and we each heard different things, and acted in different ways, based on what we heard.  “Torch Song Trilogy,” written by Harvey Firestein in the 1970s, is a collection of three one-act plays in which the main character, Arnold Beckoff, wrestles with how to live his life, as a gay man, in a post-Stonewall New York City. Central to the plot of the story, later turned into a movie, are Arnold’s relationships with boyfriends, co-workers, his adopted son, and his mother. Arnold’s mother has a difficult time accepting her son’s homosexuality, and questions why he can’t just settle down and marry a “nice Jewish girl”. Arnold is frequently agitated and unhappy with his mother’s refusal to believe that he was “made this way”, in other words, made gay, by God. In one very funny scene, Mrs. Beckoff, “Ma”, in exasperation that her son thinks he knows more about his life than she does, states, “God, doesn’t know, my son knows.”

“Torch Song Trilogy,” written by Harvey Firestein in the 1970s, is a collection of three one-act plays in which the main character, Arnold Beckoff, wrestles with how to live his life, as a gay man, in a post-Stonewall New York City. Central to the plot of the story, later turned into a movie, are Arnold’s relationships with boyfriends, co-workers, his adopted son, and his mother. Arnold’s mother has a difficult time accepting her son’s homosexuality, and questions why he can’t just settle down and marry a “nice Jewish girl”. Arnold is frequently agitated and unhappy with his mother’s refusal to believe that he was “made this way”, in other words, made gay, by God. In one very funny scene, Mrs. Beckoff, “Ma”, in exasperation that her son thinks he knows more about his life than she does, states, “God, doesn’t know, my son knows.”  The Orthodox has many rules and directives for priests. One that I frequently violated was serving the Divine Liturgy from memory and not reading from the service book. The sacred services of the Church are quite beautiful and deeply rooted in Scripture as well as the writings of the Holy Fathers. The words and symbolic gestures used in the Divine Liturgy in particular recall for us the life of Christ and his salvific work for those who believe in Him. From the prothesis (proskomedia or offering preparation) which embodies the place (the cave) and time (Christmas) of the birth of Christ, through the Lord’s ascension and His promise to return represented by the blessing the faithful with the chalice after receiving the Eucharist – we are invited to participate in the truth that is Jesus Christ and the beauty that is the Orthodox Church.

The Orthodox has many rules and directives for priests. One that I frequently violated was serving the Divine Liturgy from memory and not reading from the service book. The sacred services of the Church are quite beautiful and deeply rooted in Scripture as well as the writings of the Holy Fathers. The words and symbolic gestures used in the Divine Liturgy in particular recall for us the life of Christ and his salvific work for those who believe in Him. From the prothesis (proskomedia or offering preparation) which embodies the place (the cave) and time (Christmas) of the birth of Christ, through the Lord’s ascension and His promise to return represented by the blessing the faithful with the chalice after receiving the Eucharist – we are invited to participate in the truth that is Jesus Christ and the beauty that is the Orthodox Church.  One of the things that good teachers know is that there is no such thing as a stupid or wrong question from their students. To suggest to a student otherwise is to immediately shut down the possibility of further learning by the student. Every teacher has encountered numerous instances in class when a student raises their hand and begins with one of these phrases “I know this is a stupid question… OR… I am probably wrong but…” It takes a lot of courage for many students to raise their hand, risking judgment by their teacher as well as their peers, to ask a question that might be perceived by others as a stupid one or the wrong one. To dismiss that student’s question is the complete opposite of what teaching is all about. The Socratic method of teaching, based on asking and answering questions, promotes critical thinking and draws out new ways of thinking and understanding.

One of the things that good teachers know is that there is no such thing as a stupid or wrong question from their students. To suggest to a student otherwise is to immediately shut down the possibility of further learning by the student. Every teacher has encountered numerous instances in class when a student raises their hand and begins with one of these phrases “I know this is a stupid question… OR… I am probably wrong but…” It takes a lot of courage for many students to raise their hand, risking judgment by their teacher as well as their peers, to ask a question that might be perceived by others as a stupid one or the wrong one. To dismiss that student’s question is the complete opposite of what teaching is all about. The Socratic method of teaching, based on asking and answering questions, promotes critical thinking and draws out new ways of thinking and understanding.